The McWherter surname is an Anglicized form of the Gaelic “Mac Chruiteir,” a patronymic created from the occupational byname “Cruiteir,” or “a player of the crwth,” a musical instrument that figures prominently in the name’s early history.

As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 803 people in the entirety of the United States with the McWherter surname. That number was down from the 2000 census when McWherters reached 890 individuals. According to forebears.com, the largest populations of McWherters can be found in California, Illinois, and Texas, with broad distribution across the United States, ranging from Alaska to Florida. The only states without a record of McWherters in recent residence are Hawaii, the northern Great Plains states, and northern New England.

Variants of the Original Name

The spelling of the original MacChruiteir, when Anglicized, took many forms including MacWhirter, MacWhorter, MacQuirter, MacWherter, MacChruiter, MacWater, McWhorter, McWhirter, MacQuarter, MacChurter, Mcwerter, and, of course, McWherter. There are many other names that also derive from this source given the levels of literacy when records first began to be maintained. When folk provided their names to debtors, assessors, etc. the names were often phonetically recorded based on the pronunciation of the holder. As such, attributions extend to names of such wild variations as MacGruder and Werd alike. Early versions of the name would likely have used the “Mac” patronymic but over time the frequency of the spellings using the “Mc” variant became dominant.

Of the many spellings, McWhirter, McWhorter, and McWherter represent the majority of families with some variant of the original Gaelic version. Families with the McWhirter spelling are often found in Scotland and have the oldest documented histories. The McWhorter spelling became prevalent for families that migrated to the North of Ireland and on to North America. The McWherter variant of the spelling (less than 10% of all McWh*rters) is a relatively late mutation of McWhorter found in records beginning in the late 18th century and used by a branch of families with origins predominantly in the Southeastern United States of America.

The Buchanan Chruiters

It is known through modern clan association that the names MacChruiter, MacWhirter, and MacWhorter are member names of The Harper sept of the Scottish Clan Buchanan and it is for the lords of Buchanan that the ancestors of McWherters served as “chruiters”, as had been the custom of Scottish lairds, in the Gaelic tradition, to appoint a personal harper who would entertain the laird and his court with poetry, song, and perform with a Celtic wire-strung harp called a clàrsach by the Scots and also with the Welsh Crwth (pronounced “crooth”) or Chruit. The role should not be confused with the popular bards of the Middle Ages. The position of a noble’s harpist was assumed by learned men who were skilled orators, wrote poetry, and also performed with musical instruments. The position came to be hereditary and the role was assumed by the son of the harper, known as the Mac a’Chruiter in Gaelic, hence the origin of the family name MacChruitier.

If one looks at the family crest, one can see the nine-stringed Scottish harp prominently placed at the head, a reference to the profession and role that would create the family name.

Several famous harpers served Scottish lairds in the 16th and 17th centuries:

- Rory Dall (Roderick Morison): Lived from about 1656 to 1714 and served as harper and bard to John Breac, Laird of MacLeod at Dunvegan, Skye[…]. He was known as ‘Gaelic Scotland’s last minstrel’ and composed Gaelic songs on various topics[…].

- Duncan MacInDeor: Served as harper to Sir Duncan Campbell of Auchinbreck until his death in September 1694[…]. He was one of the wealthiest harpers of his generation and lived in Upper Fincharne (now Fincharn) near Loch Awe[…].

- Fearchar and Gillecallum: A hereditary family of harpers who played for the Macleod chiefly household in Skye by the early sixteenth century[…].

- Ruairi Ó Catháin: A renowned Irish harper who traveled widely in Scotland, though his supposed stay with Sir James Macdonald of Sleat is unconfirmed[…].

These harpers not only provided musical entertainment but also served important roles in their communities. They often acted as witnesses to legal proceedings, carried news between households, and some, like Roderick Morison, even served as tacksmen managing estate lands[…].

Given the large land holdings that late-medieval McWhirters enjoyed especially in present-day Ayrshire and Dumfries and Galloway, suggests that they had indeed evolved into “tacksmen”, intermediaries between nobles and peasants who managed the land and paid a “tack” to their lord, a role peculiar to Scottish societies.

The Family Motto

“Te Deum laudamus” is the family motto, given in Latin, and translates to “Thee, oh God, we praise.” The phrase was made popular in the 4th century Church by the hymn of praise titled ‘Te Deum’. The chant remains part of the Roman Catholic observance after these many centuries.

Insular Celts

Thanks to advances in genetic testing, McWherter men can trace their DNA back to a shared haplogroup that emerged during the Early Bronze Age in Britain and Ireland, R-L21. Growing evidence associates R-L21 with various hereditary lines to Scotland and the House of Stuart and to Irish dynasties including the Dál gCais clan, the Eoganacht dynasty, and the Connachta dynasty.

This genetic ancestry can be traced further back, via the Connachta, to haplogroup RM-269, associated with the Uí Néill dynasty, whose name means “descendants of Niall,” and who are ostensibly traceable further back to just one man who bore haplogroup R-M269, at one time thought to be Niall, King of Tara in northwestern Ireland in the late 4th century C.E. Men associated with the Uí Néill shared common ancestry with R-L21, but R-L21 is considered an extension of a shared lineage.

It is uncertain how the McWherters’ forebear made his way to Scotland but it seems likely that some combination of raiding, trade, and attempts at colonization by people associated with adventurers like the Uí Néill dynasty figure prominently in the story. Gaelic influence more formally emanated from northern Ireland beginning in the 5th century with the establishment of the overkingdom of Dál Riata which would ultimately form the noble origins of the Kings of Scotland when the Dál Riatan Kings merged with Pictland to form the Kingdom of Alba, the nascent Kingdom of Scotland. During this time trade and migration were a common occurrence across the North Channel, the strait between north-eastern Ireland and south-western Scotland.

A possible path might be established in the origins of clan Buchanan itself. The story goes that one Anselan O Kyan, a son of Okyan, a provincial king of south Ulster in Ireland, landed on the coast of Argyll in 1016. It is purported that he entered the service of the High King of Scotland, Malcolm II, in his second invasion of Bernicia, a holding of the Danes in Northumbria. For his service, he received land in Buchanan parish, which lies to the east of Loch Lomond around the village of Killearn.

We can’t be certain whether the future Mac a’Chruiter traveled with Anselan O Kyan or that they participated in the invasion of Bernicia in 1018. What we do know is that the Chieftains of Clan Buchanan would expand their holdings in the area by becoming senior members of the court of the Earl of Lennox. In 1296, chieftain Maurice the 10th of Buchanan, refused to sign the Ragman Roll, a document swearing allegiance to the English King Edward I. This placed the Buchanans in open rebellion against the English King. The clan’s chief, lairds, and all the clansmen they could muster joined under Malcolm, the Earl of Lennox, for whom they had previously served and participated in the military campaigns that would culminate in the English defeat at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314.

The Mac a’Chruiters of Carrick and the Fortunes of War

Whatever the path from Ireland to Scotland, the documented history of the McWherter ancestors emerges in the heart of Scotland, from the western reaches of the Strathclyde region and onto the eastern shore of Loch Lomond in the parish of Buchanan.

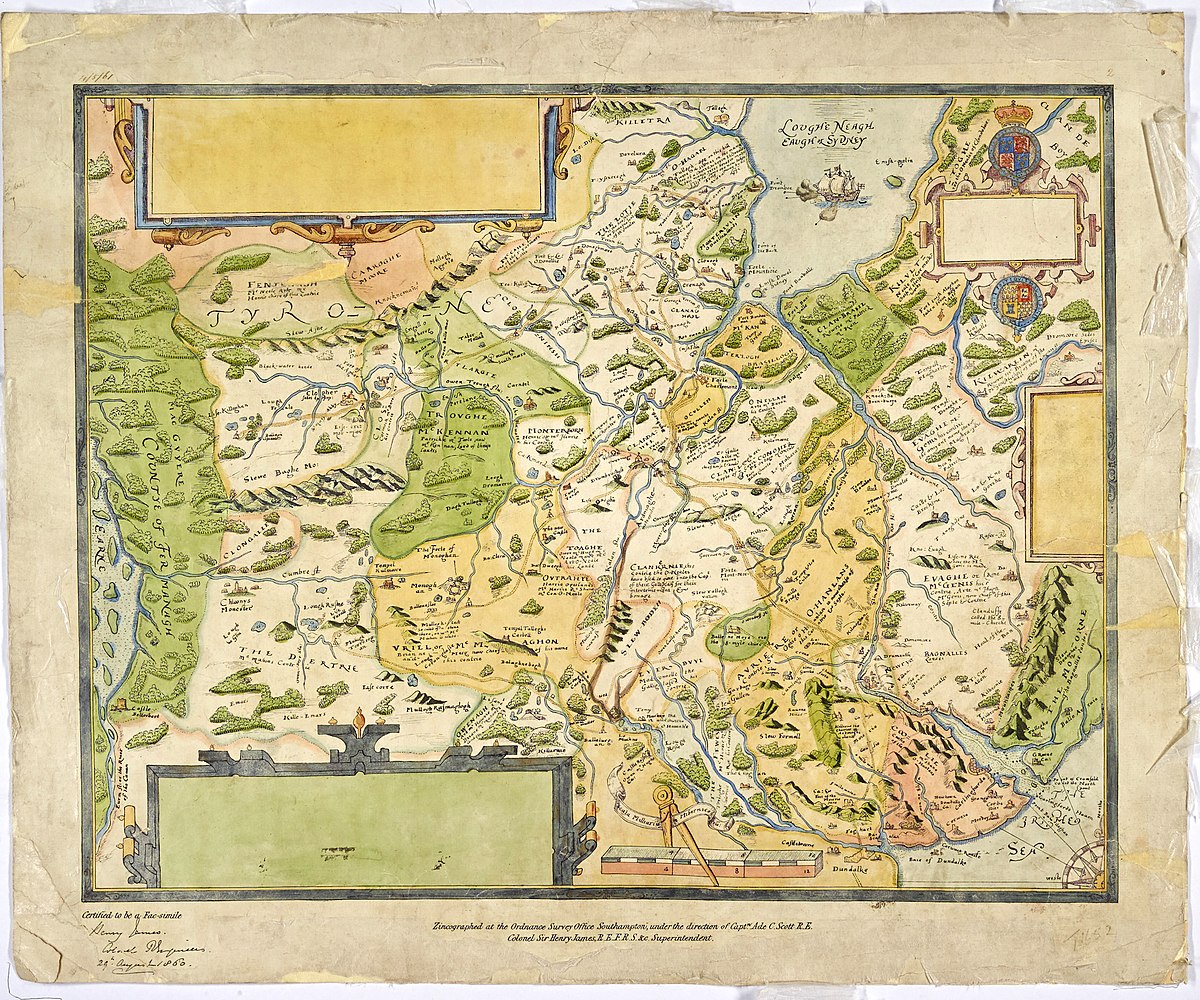

Public Domain, Link

The first written records of the Mac a’Chruiters appear in 1190, where they are referenced as the hereditary harpers of the Earls of Carrick (the Mac Citharistes) in the historical district of Carrick. References appear again throughout the 13th and 14th centuries, before, during, and after Scotland’s Wars of Independence against England from the late 13th century until the beginning of The Hundred Years War between England and France beginning in 1337.

The Buchanan clan, and the MacChruiters as their sept, supported Robert the Bruce in the Wars and it is in Robert Bruce’s former holding before becoming King of Scotland, the Earldom of Carrick, that we see the first documented evidence of the family in history. The first record of the name in any variant is found in Ayrshire, formerly the Earldom of Carrick, in the southwestern Strathclyde region of Scotland, that today makes up the Council Areas of South, East, and North Ayrshire, where the family acquired a manorial seat thanks to its association as the Citharistes (Harpers) to the Carrick family.

The first mention is a land grant that appears in the historical record for a place named Ballymontyre Contin mentioned in the 12th, 13th, and 14th centuries. From TRANSACTIONS of the DUMFRIESSHIRE AND GALLOWAY NATURAL HISTORY and ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY there is a section on page 102 describing the emergence of the name as associated with the Carrick family of Ayrshire, “It seems likely, judging from the various recorded transactions involving Ballymontyrcoueltan, that this property was held by the Mac Citharistes as hereditary harpers to the Carrick family. The exact location of Ballymontyrcoueltan is not known but its most probable location is beside the river Girvan near Straiton. The hereditary Citharistes of Carrick seem a likely origin for the surname MacWhirter (Mac a’Chruiter) in Ayrshire.”

Another document referencing the family can be found in an article describing the prevalence of the wire-strung harp in Scotland:

“Another harper who was probably playing a wire strung instrument appears during that same period in the south west of Scotland. In 1346 David II granted a charter to ‘Patrick, son of the late Michael ‘Harper’ of Carrick, *(Patricio filio quondam Michaelis Cithariste de Carryk)*, of the lands of Dalelachane, which had belonged to Andrew, son and heir of the said late Michael and brother of the said Patrick. These lands had been resigned by the said Andrew before certain nobles of the kingdom at Ayr on the 23 May 1344.

Patrick was clearly the younger son of Michael ‘Harper’ of Carrick, but from other charters, it is possible to establish several generations of that family while also strengthening the probability that ‘Michael’ was using a wirestrung harp. A Patrick McWhirter first comes into view as an adult in 1261 when the Bishop of Glasgow granted him the lands of ‘Steindal’ in the forest of Dalquhairn, Dumfriesshire for a term of five years at twenty merks yearly. A similar five year bond for the lands of Kirkcudbright was also granted for a payment of twelve merks a year. The yearly payments were to be made in two parts, one half to be paid within a week of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin, (15 August), and the other half within a week of St Andrews Day, (30 November).

Clearly this Patrick ‘McWhirter’, or *MacChruiter* could not have still been alive in 1344 so would have most likely been the father or a brother of Michael ‘*Cithariste de Carryk*’. Furthermore the ecclesiastical connection, especially the St Andrews Day payment date might account for the two saints names of Andrew and Michael subsequently being used by the family. It is also clear from another charter of 1385 when ‘Duncan M’Churterr son and heir of the late Patrick M’Churterr’ sold the whole lands of Dalelachane to Sir Thomas Kennedy, Lord of Dalmorton for twelve cows with their calves, that the family ‘name’ was MacChruiter and that the Latin term Citheriste was being equated with *Cruit* or harp. Hence by association that the said ‘Cruit’ was more likely to have been strung with wire than gut.”

~from Mapping the Clarsach in Scotland by Keith Sanger

History suggests that many of the families associated with the early MacChruiters enjoyed a period of good fortune in having acquired property and the collective favors of the Church and the King. From the thirteenth to the seventeenth centuries McWhirter families can be found in records establishing their livelihoods throughout the southwest of Scotland, particularly in the areas around Maybole in Carrick and the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright in the west of Galloway.

A fascinating example is the McWhirter family that built a tower house in 1346 on the “Waters of the Girvan” near Straiton in Carrick and lived there until 1573 when the property was assumed through marriage by the Kennedy clan. The tower was ultimately absorbed into a much larger structure that is today known as Blairquhan Castle, though a careful eye can find seeming remnants of the McWhirter dominion in the reuse of a portion of the original tower in the Regency castle’s facades. A sculpted figure strumming a chruit is an excellent example.

By Jonathan Oldenbuck – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, Link

A cursory search of the area around the village of Straiton, the location of Blairquhan Castle and the elusive Ballymontyrcoueltan, yields several businesses associated with the McWhirter surname.

It is clear from these historical records and from current searches that the Scottish McWhirters had established themselves as the landed hereditary harpers of a noble house associated with the Earl of Carrick, a title that was created just four years before the first mention of MacWhirter in historical records in 1190, and they remain part of that community to the present day.

The lowlands of Scotland entered a time of relative stability by the mid-14th century, having dealt with England’s incursions, and over the next two centuries, the Scottish crown was occupied with fending off pretender heirs, securing lands through marriage, and the weakening of highland nobles who sought to remain independent of the growing strength of the upstart crown. The border with England, to which early McWhirter families were precipitously close, was an unstable region with Scots and English alike raiding back and forth, and the occasional English foray into Scotland to reduce the raiding would result in the occupation of Scottish territory by the English.

Given the relative success of these McWhirter families and the limited number of Gaelic gentry to serve, family trades spread to areas other than the playing of the clàrsach, probably divided between ecclesiastical pursuits, of which there are numerous examples by the 17th century, and more so the cultivation of the land for subsistence and trade in local markets. The hereditary role of the harpist began to fade from the courts of Irish and Scottish nobility and the bardic schools where harpists trained in the tradition disappeared by the end of the 17th century.

From McWhirter to McWhorter: the Ulster Scots

The 16th and 17th centuries saw the fortunes of the Scottish people challenged by several religious, economic, and political events.

The Protestant Reformation began to spread through Scotland and civil strife became commonplace as the Catholic Church sought to quell the Calvinism that was being embraced by many Scots. Anglicanism was at one point endorsed by the Scottish crown and an attempt to enforce its application was made, which served to deepen the sense of the loss of Scottish identity among the population. These divisions grew and lead to a Scottish civil war that was one of many that gripped the entirety of the British Isles.

Scotland’s agricultural economy fell on particularly hard times beginning in the latter half of the 16th century, with half of the harvests failing between the 1560s and the 1640s. At the same time taxation increased, the Scottish currency was devalued, and inflation drove the cost of goods upward. And to further undermine the health and wealth of the people, the plague broke out across Scotland’s central belt, from Glasgow to Edinburgh.

In 1603 James VI, the King of Scots, through inheritance became the King of England, titled himself King James I and set about attempting to create a new imperial throne of Great Britain that encompassed the kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland. Part of this strategy was to sanction the colonization of the north of Ireland in order to diminish the anti-crown sentiment which was particularly heightened in Ulster. Planters primarily from the Scottish lowlands and both sides of the English border were given the opportunity to begin a new life on new lands across the Irish Sea.

The McWhirters found themselves at a crossroads and events were set in motion that would, as was the case for so many Scots, see many of them removed not only from Scotland but from the British Isles altogether.

The Covenanters

In the latter part of the 16th century, Presbyterianism, a form of Calvinism based on the principles of the Reformation, had firmly established itself in Scotland. The Catholic Church strenuously responded in an effort to quell the growth of the religion which only served to further the movement’s agenda. As the Church persecuted those who strayed from the faith, Protestants began to form a distinct cultural identity and political will.

In the 1550s, the first Covenanters, bands of Scots bound to the Presbyterian doctrine and polity by oath, began to form and in 1581 sufficient strength of numbers lead to the public denunciation of the Papacy and the Roman Catholic Church. Indeed the rising tide of anti-Catholic sentiment was such that the Church of Scotland and King James VI, seeing an opportunity to continue an existing policy that sought to diminish the power of the Church in Scotland, adopted the tenants of Presbyterianism as the basis for the state religion and the Scottish people were enjoined to worship as Presbyterians. In 1603, with the ascension of King of Scots James VI to the English and Irish thrones, Roman Catholicism remained intact in the Highlands, Presbyterianism dominated the Lowlands, and Anglicanism began to hold sway over the King who needed to legitimize his reign by adhering to the precepts of the powerful Anglican Church.

By the early 17th century the stage was set for open conflict. Beginning in 1639 the religious identities of the people of Ayrshire, the ancestral home of the McWhirters, would be tested by war and the fate of many driven by its outcome. In 1679 the Southwest of Scotland and the many McWhirter families that lived there would face a period known as The Killing Times. A stronghold of Covenanter support, the region was plunged into open rebellion against the English and Scottish crowns. McWhirter Covenanters were present at the doomed Battle of Bothwell Bridge (listed as John M’Whirter).

The historical records indicate that McWhirter family members appear as Covenanter fugitives and rebels. One John McWhirter of Caldons was executed as a Covenanter fugitive. Another John McWhirter is memorialized after having died at sea off the coast of Orkney while being transported as a captured rebel and condemned slave to the North American plantations.

The Plantation of Ulster

By Public Record Office of Northern Ireland – https://www.flickr.com/photos/proni/27484911573/, No restrictions, Link

With James VI’s inheritance of all three Kingdoms of the British Isles, two prominent Scottish lairds of Ayrshire, Hugh Montgomery and James Hamilton, prevailed upon the King to free an imprisoned Irish noble, Gaelic chieftain Conn O’Neill, who had offered in exchange for his release to divide his lands in Ulster between Montgomery, Hamilton, and himself. The King, owing a debt to the men who had been instrumental in his accession to the throne, agreed to free O’Neill.

Montgomery and Hamilton recruited tenants from the Lowlands and in particular their extended relations in Ayrshire. It is likely that McWhirter families were among the farmers, artisans, merchants, and chaplains that made their way to Ulster in 1606 as part of the pair of adventurers’ scheme.

The establishment of what were effectively colonies of Scots in Ulster was successful and illustrated a model that would form the basis of a government-sanctioned Plantation scheme in which Scots and English from the unstable border region between Scotland and England would be recruited as low-rent tenants of the lands of Irish nobility who, rather than submit to English rule, relinquished their lands and left Ireland for Europe. In 1609 James VI enacted his plan to both diminish the threat to the stability of the English border by depopulating it and at the same time increase the integration of his Kingdoms in the notoriously anti-English region of Ulster.

If McWhirter families were not involved in the original adventure established by Montgomery and Hamilton, they were certainly involved in the Plantation scheme that followed as we know of several McWhirter families that lived in the vicinity of Armagh in the Ulster Plantations. It is at this time that we begin to see the emergence of the McWhorter variant of the name in wide use.

The McWhirter Diaspora

Imagine what life must have been like for the McWhirter families in Scotland at the beginning of the 17th century. The border with England, a mere sixty miles away, was essentially lawless with neither Kingdom able to fully exert control over the population on either side of the border. The Scottish land, already difficult to work in the best of times, was failing to produce crops. The economy of Scotland was suffering massive inflation and society was experiencing religious turmoil at all levels. Many McWhirter families, having declared an oath to the Covenanters entered into a state of rebellion against the crown.

And then there was the promise of a new life across the Irish Sea, away from the Scottish crown which was attempting to force the conversion of the Covenanters to the Anglican Church. It is little wonder then that the late Shelley McWhorter Wright, in her book on the history of her family wrote:

“It was during the Plantation of Ulster (1606-1610), and the years immediately following, that the McWhirters–practically all of them–left Scotland for a new home in Ulster, the exact time of removal, my research has failed to disclose. At least a few of them remained in Ayrshire for some years, as John McWhorter was at the Battle of Bothwell Bridge in 1679. But it appears that all of them finally followed the Clan to Ulster–my research failed to find the name in Scottish histories or records after 1700.”

A considerable number, perhaps the majority, of the McWhirter families in the southwest of Scotland migrated to the north of Ireland at the beginning of the seventeenth century. And for those who remained in Scotland, religious and civil strife would lead to war and an uncertain future as fugitives of the law in many cases.

As far as can be understood, the plantation effort in Ulster was successful, the land was productive, and the colonists, including the McWhirters who left their homeland for a better life, enjoyed a brief period of prosperity.

But even the Irish Sea could not provide sufficient respite from the growing turmoil in Scotland. With the succession of the three kingdoms, England, Ireland, and Scotland, to the son of James I, Charles I, and a doubling of the effort to enforce Episcopal authority over the Presbyterians, religious and political tensions in Scotland became open Scottish rebellion against the King’s authority. In 1639, Charles I responded with an invading army and thus the Wars of the Three Kingdoms began and continued until 1651. In that period hostilities broke out in all three of Charles I’s kingdoms.

Of particular consequence to McWhorter families in Ireland, for the records show a change in the generally used spelling perhaps to distance themselves from their rebellious acts, was the Irish Rebellion of 1641 in which the Catholic Irish rose up against crown authority and began massacring the English and Scottish Protestant tenants of the Plantations in nothing short of ethnic cleansing. An example of just how unfortunate this moment was for the families involved is captured in birth and death records. The Reverend Alexander McWhorter II was born in 1641 to the Reverend Alexander McWhorter I and death records show that the younger Alexander’s father, mother, and grandfather all died in 1641.

There is a family story that Alexander McWhorter I “came to Ulster with his family and settled in Londonderry. In one of the uprisings, almost all the Ulster McWhirters were massacred in 1641. The Catholics broke into their home and killed everyone except for a newborn baby who was upstairs with a maid. She spirited the baby out of the house and either took him back to Scotland or to other family members who lived in Ulster outside of Londonderry who then took him back to Scotland. The baby was probably also named Alexander. It seems as though this second Alexander as an adult went back to Derry.” There is some doubt regarding the details of this recounting, primarily because there is evidence that the actual location in which the McWhorter family died was in the town of Cavan in County Cavan, which had fallen to rebel forces within a week of the uprising and it is well-documented that the Reverend Alexander McWhorter II, upon returning to Ireland decades later, established himself in the city of Armagh. If the story is apocryphal in the specifics, in general, it is a truth that this branch of the family suffered a calamity in 1641 that very nearly extinguished the most historically documented line of McWhorters who would ultimately immigrate to the American Colonies, a line that directly descends from the very fortunate Reverend Alexander McWhorter II.

The American Colonies Beckon

Perhaps the best-documented evidence of McWhorters in Ireland is that pertaining to one Hugh McWhorter. Born 1670 in County Armagh to the Reverend Alexander McWhorter II and Phoebe Bruen McWhorter. He was married in 1710 at County Armagh to Jean Gillespie, the daughter of Andrew and Mary Gillespie of Clackmannan, Ayrshire, Scotland. By occupation, he was a successful Linen Merchant. Following the Plantation of Ulster, there was a boom in trade with England for linen products. The introduction of flax farming in Ulster provided a ready source of raw materials and over 30,000 households in the region were engaged in production by the end of the century. By 1705 the trade with England was expanded to the newly established colonies in North America. ~ The Ulster Linen Triangle

It is not entirely clear what drove the decision, but in 1729 Hugh, along with his wife and children, several of whom were adults with families of their own, emigrated to the American colonies. What is known is that the Penn family, heirs to William Penn and owners of the land that would eventually become Pennsylvania and Delaware, were actively recruiting Irish settlers to the American frontier in an effort to hedge against the encroachments of other colonists from Maryland and to displace the indigenous inhabitants. After arrival, Hugh settled his family on farmland in Pencader Hundred, located in New Castle County where he resided, an extensive and successful farmer, until his death.

Life on the Frontier and the Emergence of the McWherters

It is known that a number of Hugh’s sons, among them George Barnett McWhorter, struck out from Delaware to head south in search of their own fortunes. As the colonies continued to expand westward from the Atlantic coast, the land was opened in western Virginia at the foot of the Appalachians. George McWhorter was old enough at the time of his migration to the colonies to have already married and had several children and while historical records are relatively silent regarding George himself, there is ample evidence regarding his son, John McWhorter, who appears in records in Albemarle county in 1745 and was involved in several land transactions around present-day Rockfish, Virginia. John McWhorter was married to Eleanor Brevard and they had several children including one John McWhorter, Junior, born 1749.

John Senior died in 1757 leaving his widow and children his lands. In 1766, Eleanor McWhorter was granted lands along the Packolate River by William Tryon, then Governor of the province of North Carolina. She sold the entirety of her late husband’s holdings and the following year moved her family to present-day Union County, South Carolina. The family remained there opening the frontier for development.

As the rumblings of revolution took hold in the northern colonies, the famous reverend Alexander McWhorter, an impassioned Presbyterian minister and also Delaware great-uncle to the Carolina McWhorters, being the sibling of their grandfather George McWhorter, began to agitate on behalf of the Independence movement, even traveling in 1775 to North Carolina to spread revolutionary fervor on the southern frontier. John McWhorter Junior answered the call by joining the North Carolina Line of the Continental Army in 1775 and served until 1781. He likely served in the 1st Regiment in which he saw action on several occasions including the Snow Campaign, the Bush River Campaign, and the Siege of Ninety Six to name but a few. He mustered out in 1781.

When next the historical record mentions John McWhorter Junior, his family is again on the move. In 1796 John is recorded as having sold all of his lands in the Carolinas and in 1798 he appears again in the records as having purchased a large amount of land on the western frontier, part of the Great Migration, along the Green River near present-day Middleburg, in the newly created 15th American State, Kentucky. John would continue his life as a successful farmer there until his death in 1833.

It is during the lifetimes of John McWhorter Senior and John McWhorter Junior that records begin to reflect a change in the spelling of the family name, from McWhorter to McWherter.

Birth of a Nation, Birth of a Name

By the time that James McWherter is born to John McWhorter Junior, along the Packolate river in 1776, the McWherter spelling enters the record, and every child born to John McWhorter Junior’s family line after the migration to Kentucky is identified with this spelling. So it seems that the birth of James McWherter not only coincided with the birth of a nation but also the birth of a name.

James McWherter would die before he turned thirty, his wife having died five years earlier, leaving their two sons, Benjamin Franklin and George Washington McWherter, orphaned. Upon their father’s death, they were sent to live with family members located even further west, in the plains that approach the mighty Mississippi, in Weakley County, Tennessee.

McWherter families would remain largely in the Southern and Midwestern states of the United States, primarily as farmers until the middle of the 20th century when first the depression found many Americans leaving their farms in search of work in the cities, and then the second World War would spark massive migration to manufacturing centers and coastal cities to participate in the war economy. After the war, some McWherters would go on to figure prominently in Tennessee politics, culminating in Ned Ray McWherter becoming the 46th Governor of Tennessee.

As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 803 people in the entirety of the United States with the McWherter surname. That number was down from the 2000 census when McWherters reached 890 individuals. According to forebears.com, the largest populations of McWherters can be found in California, Illinois, and Texas, with broad distribution across the United States, ranging from Alaska to Florida. The only states without McWherters in residence are Hawaii, the Great Plains states, and northern New England. So broad a distribution for a family so small in numbers. It seems that the wanderlust that inspired the early McWhirter Scots to begin their adventures in Ireland, then the McWhorter Scots-Irish to journey on to the American colonies, and then to pursue an ever westward course, remains a trait for the modern bearers of this young surname. A young name for a young nation.